My dearest spectral locomotives:

Summer is almost here! It finally fucking stopped raining in San Francisco! Praise Karl! My son said to me, “Weird, I don’t get your newsletter anymore,” and I was like “uhhhh it’s because I haven’t written one” so I decided to make up for that with 7,000 words about the horrifying human cost of migration to America through Panama. We got macabre details and political grandstanding aplenty, so grab your DEET and let’s get into it.

Immigration is back on the front page of America’s news outlets, with the expiration of Title 42 and an expected rise in border crossings. Title 42 is an emergency health order that allowed the US to turn asylum seekers away at the border, ostensibly to prevent the spread of COVID 19. It was activated by President Trump and continued by President Biden, who then allowed it to expire last week. For the record, US immigration law allows anyone seeking asylum to enter the US and wait for a hearing to determine eligibility. Calling these people “illegal” is a misnomer; if a person came here and requested asylum, they are legally allowed to stay until their case is adjudicated. And in case you don’t know, most of them are denied. It’s heart-breakingly difficult to meet the asylum threshold here.

Coverage has focused on the dangerous route that migrants are taking to get to the Southern Border, on foot through the Darién Gap between Colombia and Panama. The “gap” is the section of land that is missing from the Pan American Highway System – the land was simply too rugged to build across, so when I say they are coming on FOOT, I mean THEY ARE ACTUALLY WALKING THROUGH THE JUNGLE. On foot through a place so treacherous that North and South American governments left a 66 mile stretch unpaved in a system that spans 18,000 miles. You might call it the most dangerous, impassable section of land on these two continents. And hundreds of thousands of desperate people are crossing on foot escaping violence and poverty.

The Darién has been called “a nightmare with 1001 demons.” On the footpaths there, people can expect to encounter dense vegetation, high rivers, flash storms and floods, deep mud, trash, insects and WHO KNOWS WHAT that lives in a mountainous jungle. Snakes? Jaguars?? Poisonous Spiders!!! Besides indigenous locals, the forest is full of drug smugglers and other unsavory criminals who rob, rape, intimidate, and extort the people passing through. Dead bodies are littered along the route, and migrants have to pay opportunists at every turn: to cross a river, to camp, to be released. The Gap is awash in human bravery and hope, but also in suffering: mud covered humans with multiple injuries, carrying and often losing what little they have. Elders die of exhaustion, babies are swept away in rivers, families get lost and separated.

As someone with a head full of the darkest moments of colonial and westward expansion in the Americas, I’m here to tell you that Panama has always been central to getting to the United States, and it’s always been fucking dangerous. Reading the coverage of the current migrant crisis has resurrected the horrors of the overland passage through the isthmus of Panama, the Panamanian Railroad, and the building of the Panama Canal. The road to a dubious freedom in the US has long been littered with bones.

Before the Panama Canal, ships traveling West could cut the journey short, avoiding the trip around Cape Horn, by going overland through what is now Panama. Sailing to the Caribbean side of the Isthmus, then trekking across the narrowest part of the Continent and boarding another ship on the Pacific side was faster than either of the other two routes west – on wagon train overland through North America or sailing around South America. This route was most frequently used for communication – news, mail, and important business that could not wait. When the Gold Rush began in 1848, and time was of the essence, the Panama route became very popular.

Popular and dangerous! Travelers would take dugout canoes piloted by locals up the Chagres River, then switch to mule trains for the remainder. It took ten or eleven days, and it was full of peril. Lack of sanitation and infrastructure, combined with tropical mosquitoes, spread diseases like cholera, typhoid, malaria, and yellow fever. Mules carried travelers over narrow, steep mountain passages, and machinery and equipment were frequently lost. Opportunists extorted money at every juncture, and people were frequently left behind on the Pacific side if their trek took too long. Ulysses S. Grant took a company of soldiers and civilians across the Isthmus in 1852, and more than half of them died of cholera.

It didn’t take the railroad barons long to figure out there was some serious money to be made with a line across the Isthmus. In 1855, an American investment group called the Panama Railroad Company began construction on an inter-oceanic railway line. This was a massive and dangerous undertaking – workers had to clear and fill swampland and jungle, contending with alligators, mosquitos, and disease. They had some steam powered equipment, but most of the labor was done by hand by people from the Caribbean, Ireland, India, China, and Australia. Cholera, yellow fever, malaria, accidents, heat, and PROBABLY poor management killed 6,000 – 10,000 workers.

“The working conditions in those days were so horrible it would stagger your imagination,” recalled laborer Alfred Dottin. “Death was our constant companion. I shall never forget the train loads of dead men being carted away daily, as if they were just so much lumber.”

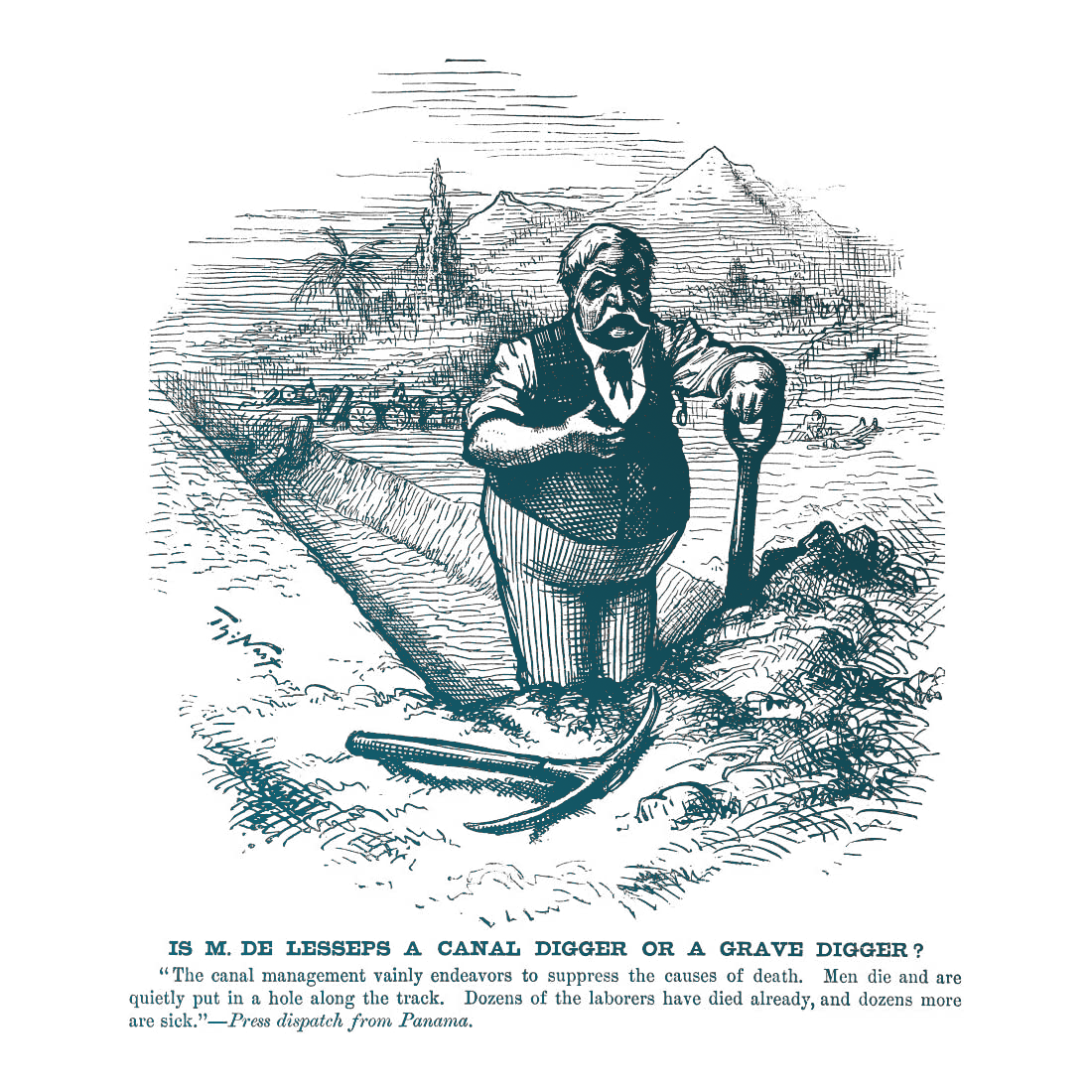

That is a lot of death BUT ALSO amateur hour compared to the construction of the Panama Canal, generally accepted as one of the most deadly construction projects in the modern era. 25,000 workers died building the canal, an astonishing number that some experts think was actually higher. There are a ton of documentaries about the construction of the canal – I’ll link them below – but to recap, all of the dangers of dynamite, machinery, jungle, swamp, flooding, and careless treatment of workers were magnified by the sheer number of people required to hack a canal across 60 miles of rough terrain. Most of the workers were from the West Indies, and most of them were Black. A contemporary journalist remarked that “human life is the cheapest article to be purchased on the Isthmus.”

One claim that I’ve seen circulated is that there were so many dead bodies that the construction firm would put them in barrels full of liquor, pickle them, and sell them to medical schools for use in dissection labs. I haven’t been able to confirm it, but it’s definitely within the realm of possibility. Most workers were buried in mass graves, or simply rolled into the trench they were constructing at the moment, and covered over with debris. These stories reveal the deep contempt and overwhelm that French and American builders felt toward the workforce they were grinding through to create the world’s “greatest engineering marvel.” Imagining the dead as carts of lumber or plentiful fodder for the bonesaws is an extension of the horrors inflicted and endured to cross the Panamanian isthmus, and get to the American West Coast.

And isn’t that the real story of Manifest Destiny? The Panama Canal allowed The United States to flex its power over North and South America – and we’re reaping the consequences of that now. South and Central Americans aren’t fleeing here because they love blue jeans and rock and roll – their countries have been destabilized by a century of American interference and a failed war on drugs. They risk life and limb to get here only to be greeted with razor wire, anger, and conservative propaganda that vilifies them as disease carrying criminals. Politicians exploit them for personal gain, and then look the other way when farms all over the US hire undocumented people to process the food we eat every day.

It’s gothic as fuck, kids. Happy Summer!

Xo,

Court