Language is a hot topic these days. You can’t shake a stick without hitting a concerned centrist who thinks the use of the term “pregnant people” heralds the downfall of civilization. As a country, we are deep in the trenches of the stupidest culture wars to date, taking cannon fire from dudes who failed high school English but want to instruct us on the proper use of the they/them signifier. For this reason, it was hilariously disconcerting to dive into the archives on San Francisco’s worst “hospital,” which was simply called THE PEST HOUSE.

THE PEST HOUSE, you guys. The PLACE FOR THE PESTS. Who were the pests? The bacteria? The patients?? Maybe the massive colony of rats and fleas that surrounded it?? WHO KNOWS! Today’s language of marginalization – racism, ableism, xenophobia – can’t even touch the shit that was happening here, at the site of the modern day Zuckerberg General. The Pest House was a filthy, underfunded, understaffed collection of claptrap cottages where sick people were sent to die in rags. Mostly Chinese, mostly poor, mostly not an actual threat to public health.

The Pest House is long gone, but it feels to me like it left a dark imprint on the site of our largest public hospital. It feels foundational to the city and its character, in ways that echo in a more positive way through the future. We’re a city that knows plagues. We’ve been the epicenter of some serious business in the US: the bubonic plague, AIDS. Our hospitals can’t help but have been changed by those epidemics, and there is a through line from the poxes of the 19th century to the plague to AIDS and finally, to Covid. I heard nothing but derision about the city’s forceful response to the 2020 pandemic from people who don’t understand our history. We are OG, we knew what the fuck was up. And here’s a post to tell you how.

The History of Pest Houses

“Pest House” is the colloquial term for an isolation hospital. They’ve also been called leper colonies, leprosariums, fever hospitals, and lock hospitals. They’re referred to as various types of “shed” (plague sheds, fever sheds) which checks out because they were often shoddily constructed. Many were located near graveyards or mass burial sites, and almost always on the edges of town. Nobody wanted to be near a PEST HOUSE.

Isolation facilities housed people with communicable diseases – anything from leprosy to poxes of all kinds. The idea of preventing the spread of disease is good, but the execution was uh, kind of like an actual execution. People didn’t tend to recover from nasty diseases like smallpox or syphilis back in the day, so there wasn’t a lot of actual care to provide – maybe some food, maybe a fire. The municipalities didn’t want to waste money on caring for the walking dead.

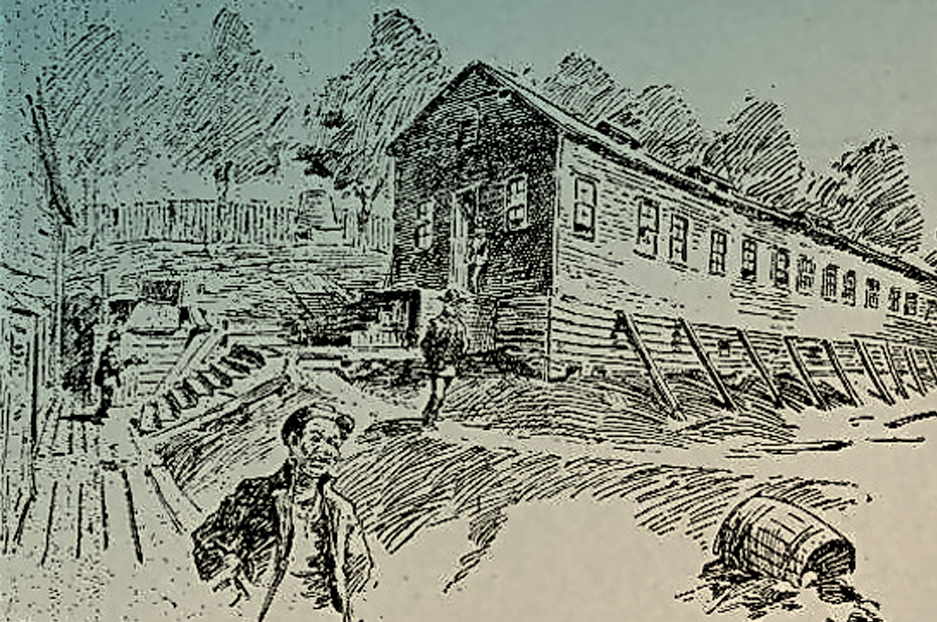

An 1896 etching from the San Francisco Call of the San Francisco Pesthouse Annex

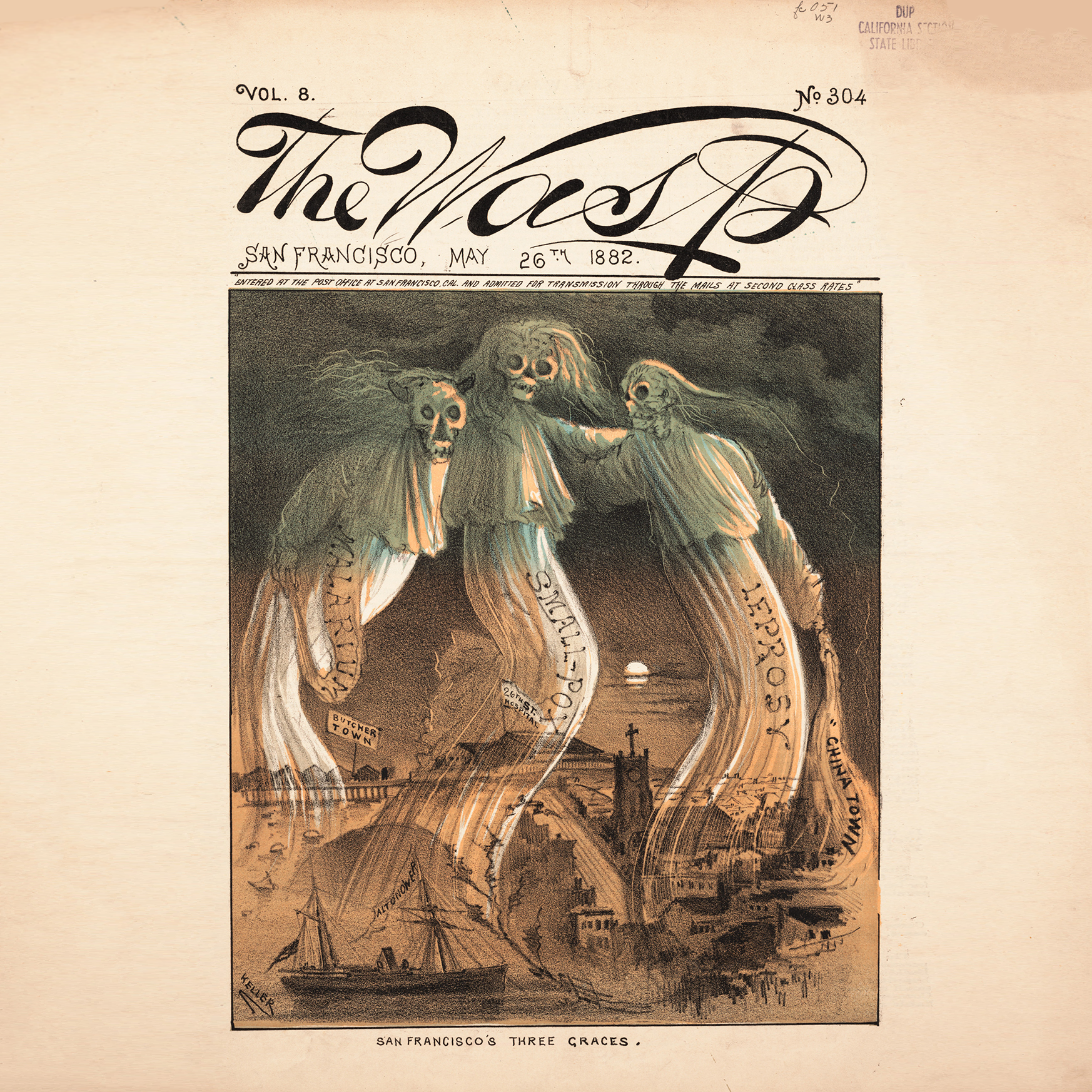

Pest Houses were the “domain of disgust.” Most of the patients there suffered from “loathsome” diseases – disfiguring illnesses that could be seen on their person. Smallpox, syphilis, and leprosy were the most common pest house diseases, showing up in sores, necrosis, and lesions on the patients’ skin. These illnesses varied in their virulence and transmissibility, but the public panicked at the thought of contracting them, they were so horrifying. The patients evoked disgust and fear, and a pest house was a place to keep them out of sight.

The 26th Street Pest House

The first hospital in San Francisco was the US Marine Hospital, built in 1851. That hospital was located near the Presidio, and it was acquired by the City in 1855. Fun fact – there’s an old graveyard on the site that houses at least 600 sets of remains AND those remains were used in anatomical dissection, but that’s for a later post!!

The Sisters of Mercy established a hospital in what is now North Beach in 1854. The Sisters arrived from Ireland after nursing the public there through a cholera epidemic. They opened a hospital that would later become St. Mary’s Medical Center (now on Stanyan near the Park), which was partially funded by the state and county and offered care to the indigent. Side note: St. Mary’s used to advertise a 30 minute or less wait time at their ER, and I went there one night for a concussion check (HOCKEY), instead of the bougier CPMC or the larger UCSF because I thought – 30 minutes or less! Like Domino’s! My husband strenuously objected as soon as we pulled up to see one patient deep in the throes of a meth bender fighting a paramedic and another one throwing up in front of the door. Reader, they fast tracked me not because of this 30 Minute thing, but because I was the only sober and sane person in there at 11pm. The charge nurse took one look at me and was like – get in here. It was FINE, I was not concussed! And now I go to CPMC, lol.

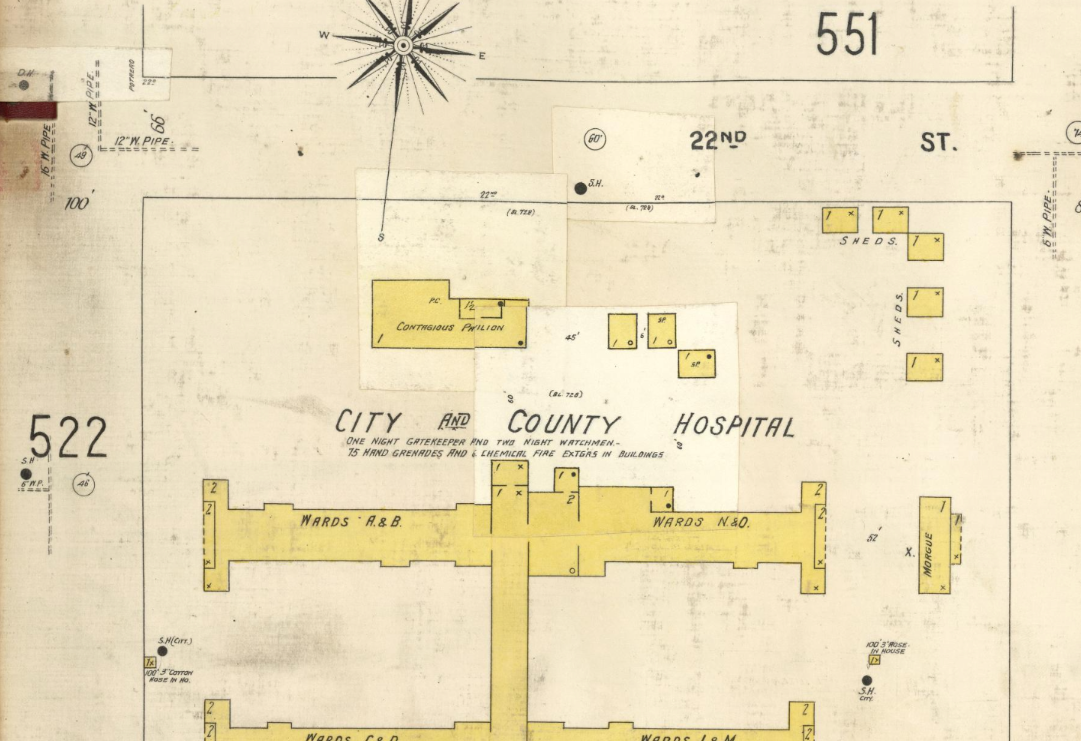

In 1857, the City and County of San Francisco established its own General Hospital, also in North Beach. In 1872, it opened a Hospital on Potrero Avenue, at the site of modern day San Francisco Chan Zuckerberg Facebook Instagram Metaverse General Hospital. Famously, the doctors have no legs. This is where most of the indigent citizens were treated, and in 1908, during the second Bubonic Plague outbreak, the city BURNED IT TO THE GROUND BECAUSE IT WAS INFESTED WITH FLEAS AND RATS. In 1915, a new hospital was built on the site, and the bones of that structure still stand as the gothic industrial temple to public health that we know today.

In 1867, San Francisco opened the Almshouse at Laguna Honda. The Almshouse was more of a care facility for poor and incapacitated people than a hospital, but it did provide its residents with medical care. That site is now the Laguna Honda Hospital, a public long term care facility, currently embroiled in a licensing scandal that is impacting the care of its residents.

These hospitals tended all manner of diseases and ailments, but certain infectious diseases were seen as too hazardous to treat in mixed company. The public health dictates of the time called for quarantine and isolation, which ushered in the era of the Pest House. The first quarantine shack was set up in 1850 in Chinatown, for potential cholera victims. In 1852, it moved to the Clarendon Hotel on Stockton Street. In 1891, a quarantine station opened at Angel Island, where sailors showing symptoms were held and sometimes turned back. The Almhouse at Laguna Honda got its own smallpox isolation hospital in 1868.

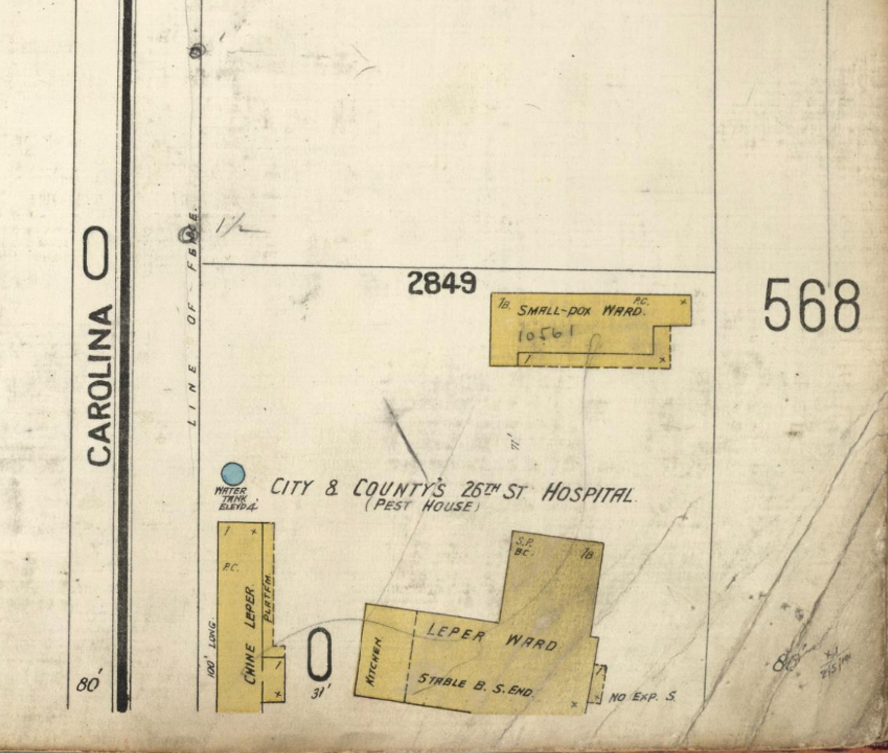

The Big Guy, though, was the PEST HOUSE, which also opened in the 1860’s. The institution went by many names – 26th Street Hospital, 26th Street Lazaretto, Smallpox Hospital, CHINA HOUSE- by most called it simply the Pest House. Locals called the area around it the Devil’s Acre, because, well, you’ll see.

The Pest House ended up in Potrero Hill because at the time, it was remote. There weren’t enough people living there to fight it. Previous attempts to install a hospital near City Cemetery and Lone Mountain were stopped by neighbors, and when a location was proposed South of Market, the community amassed a dynamite stockpile and threatened to blow it up. In case you thought NIMBYISM was something new, you guys!!!

Erected in the mid 1850’s, the hospital started as a “flimsy shack.” It was surrounded by barbed wire fences, to keep looky loos out and inmates in. A eucalyptus tree was planted to neutralize “effluvia” which is hilarious because eucalyptus smells like BO (a hill I will die on, don’t come at me on this). In the 1860’s, the Pest House was expanded with a large general ward and additional patient rooms. A “cottage” was built to house Chinese patients, because the entire place was racially segregated.

Even with the expansion, the Pest House is described in contemporary reports as rickety and decrepit. In a drawing from 1896, buildings are held up with stilts and walls appear to be caving in. The press described the premises as dark, primitive, and cheap. They compare it to a dungeon and a prison. Some rooms were heated with coal stoves, but many were not. In order to ventilate the shacks, holes were drilled in the walls. The floors were filthy and rank. A sewer main was broken and never repaired, so an open cesspit only 50 feet away from the building was used instead. The roofs leaked.

At the time of the Pest House, Potrero Hill and the surrounding areas housed factories, tanneries, slaughterhouses (it’s right near Butchertown), and garbage dumps. Which checks out because the hospital was basically a dumping ground for unsightly poor people judged to be hazardous to public health. Islais Creek flowed through this part of town, bringing with it a “hell broth” of overflowing trash, offal, and rats. A press account describes it as a “poisonous breath of pestilence, a malicious and pervasive vapor that percolates toward the blood, transverses the nerves, and finally affects the brain.” Can you imagine thinking one fucking EUCALYPTUS TREE could fix this stench???

The Pest House itself contributed to the soot and pollution of the neighborhood by regularly burning rags and bedding. Patients grew vegetables on the site but routinely urinated in the garden and fertilized it with their own poop. The walls were routinely whitewashed to kill germs but… when you’re shitting in your own food, IDK how much that helped.

Of course, this part of town was so gross that even the main hospital was a problem. From 1900-1910, San Francisco experienced a bubonic plague outbreak. Many of the rats and fleas transmitting this disease were coming out of Butchertown (just to the South). City and County Hospital, as it was then known, was a shoddily constructed wooden building, and it soon became absolutely overrun with rats. People were going in for minor things and COMING OUT WITH THE PLAGUE. Eventually, the city just burned the whole thing down and started over.

Assorted “Sheds”

The Epidemics

The Pest House took in patients with three main diseases: smallpox, leprosy, and syphilis. All of these illnesses are colloquially known as poxes, and all were visible and disfiguring. In his book, “Driven by Fear,” Guenter Risse describes the cycle of panic and scapegoating that occurred with each epidemic or outbreak: “fear, awe, repulsion, stigma, denial, rage, and blame.” Disease wasn’t theoretical in the mid to late 1800s – people weren’t debating the merits of Big Pharma’s profit margins and whether rosemary oil was better than penicillin – they were dying in large numbers. Fear is the root of most of what follows, and scapegoats were almost always politically expedient minorities.

In 1868, San Francisco experienced an outbreak of smallpox. This virus was introduced to the Americas by European colonizers, and it came to California in the 1830’s. Outbreaks continued into the 1870’s and 1880’s. Smallpox is a horrifying disease – it killed and disfigured millions of people before humanity eradicated it in the 1970s. The virus causes fevers, vomiting, and tell-tale ulcers (POX) on the skin. If people survived, they were scarred for life by these lesions. Historically, smallpox had a fatality rate of 30%, and because the disease was visible, it caused panic and scapegoating ON SIGHT. It was called “the speckled monster” and it’s probably the virus most responsible for wiping out the Indigenous people living in America.

Smallpox is a respiratory virus, so it’s spread in the air. Even before germ theory was really understood, this was known – quarantine and isolation were used to try to limit the spread. People were terrified of smallpox. Diphtheria was killing twice as many people at this time, but it didn’t get the attention because it wasn’t visually as scary.

A smallpox scapegoat emerged early on – Chinese immigrants, and Chinatown itself. The press called the disease “the Chinese ulcer.” Powerful racist and nativist forces in San Francisco capitalized on smallpox to further demonize immigrants. The notorious Workingmen’s Party (the BUILD THE WALL faction of Victorian era San Francisco) loudly and vociferously blamed Chinatown and called for the expulsion of Chinese residents. The Board of Health, joining in, declared Chinatown a “laboratory of infection” and called for it to be eradicated. (This is not the first or the last time the City will try to burn Chinatown down, by the way. They wanted that land AND they were racist assholes, it was a win win!)

The City responded by first opening a smallpox hospital near the Almshouse, and then expanding smallpox quarters at the Pest House. They employed a comically horrifying zinc-lined SMALL POX PADDY WAGON to round up the infected and incarcerate them in isolation wards. People did not want to go for this ride!!! They hid patients, removed the “yellow flag” quarantine notices on their doors, and turned to local providers instead. Like most things, poor neighborhoods like Chinatown and SOMA were oversurveilled and over-enforced. These were the people being dragged off to rot at Laguna Honda or the Pest House, not the people living in private homes on Nob Hill.

Leprosy showed up in San Francisco in the 1860’s. The first documented death from the disease was in 1869. The disease most likely traveled along trans-Pacific shipping lines. Hawaii had an outbreak of leprosy as well. San Francisco was the only city on the US mainland that had a meaningful population of lepers.

Leprosy – today known as Hansen’s Disease- is ancient, and its place in the Bible gives it outsized influence on Western people. Leprosy was associated with sin and immorality. In the Bible, lepers were unclean, and that tradition lived on for thousands of years. Of course, it’s actually caused by bacteria, NOT SIN. It is spread through contact – bacteria can invade and colonize an open wound OR through contact with mucous membranes.

Like smallpox, leprosy was a disfiguring disease that caused lesions all over the body. Untreated, it also causes nerve damage, leading people to lose the sense of touch. People with leprosy lost fingers, toes, and limbs from accidents and infections. And again, similar to smallpox, because you could SEE leprosy, it caused fear, panic, scapegoating, and overreaction. We call social pariahs LEPERS for a reason.

It’s hard to overstate how terrified people were of leprosy. It was mistakenly thought to be very contagious – it’s actually not. Less maligned diseases took far more lives, but those folks weren’t transported in zinc-lined carriages, or buried in zinc coffins covered in quicklime. I guess the POX PADDY WAGON was doing double duty! The Uber of the infected! A ticket on the ULCER MESS EXPRESS! Next stop, Hell.

Also like smallpox, Chinatown and Chinese immigrants got blamed. Famous author Bret Harte even got in on the action, faulting “the heathen Chinee.” Leprosy was associated with syphilis, and thought to be sexually transmitted, leading to further stigma and condemnation. Because Chinatown was also a vice district with busy brothels, Chinese sex workers bore the brunt of shame and persecution. It did not help that this disease was imbued with Biblical overtones of sin and punishment. It will get worse when we talk about syphilis, don’t worry!

Ironically, leprosy wasn’t actually that contagious – and it did not spread at all within the Pest House. The epidemic wasn’t really as much about the number of cases as the sheer panic it caused. The surveillance and incarceration of people with leprosy was an overreaction.

Finally, syphilis broke out frequently in the mid to late 1800s. Syphilis is an OG sexually transmitted infection. It’s caused by bacteria, and it too can be disfiguring as the disease progresses. Untreated, syphilis causes ulcers and tumors all over the body. It can attack the brain and nervous system in its late stages, causing severe mental illness. It was called “the Great Pox” for a reason. The disease was primarily associated with sex and sex workers – making visibly affected people pariahs.

Syphilis was endemic in San Francisco, spread mostly by sexual contact at brothels. And while there were brothels all over the city, the public health department and the public saved most of their scorn for Chinatown. Chinatown was both a racial ghetto and a vice district. Chinese immigrants were forced to live within its confines, but white people could come and go. Brothels were tolerated there, and they were used by both residents AND white men from outside of CT.

The brothels were NOT NICE PLACES, and the women who worked there were essentially trafficked from China and put to work with little say in the matter. Like sex workers all over the state, they faced abuse, infection, and poverty. In 1880, the public health department declared Chinatown a nuisance, blaming it for the rampant syphilis in San Francisco. Like leprosy, plague, and smallpox, Chinese immigrants and Chinatown specifically were blamed.

Before penicillin, there was no treatment for syphilis. By the time sex workers showed symptoms, they had already infected dozens of men. They were thrown out and many ended up at the Pest House Annex. The Annex was described as a “cottage” on the 26th Street Hospital property, and Chinese sex workers were confined there. This type of unit was called a “lock hospital” – patients were locked in to contain spread of the disease. Lock hospitals almost exclusively involved STIs.

Cottage is a cute word for what was a ramshackle hut crowded with suffering inmates, unable to leave. It was segregated, but like the other diseases, Chinatown and Chinese residents were over surveilled and incarcerated. In other words, there weren’t that many white people to lock up there.

Modern Epidemics

The Pest House eventually closed, and medicine and society evolved past rundown isolation cottages, but old prejudices against the sick died hard – especially when they involved sex and marginalized populations. In the early 1980’s, San Francisco emerged as the epicenter for a new viral illness that would eventually turn into a tragic national epidemic: AIDS. Out of the ashes of that terrible plague grew a compassionate, science-based, civil rights focused response in our city. I keep telling you guys, the phoenix is in our city crest for a reason.

When AIDS came on the scene in 1981, it was a total mystery. Young, healthy gay men were developing ailments seen in older, sicker people – Kaposi’s sarcoma, pneumocystis, fungal infections, and eventually dementia and death. Researchers saw the link in the gay community, but had no idea how it was being transmitted. It was called gay cancer, with the KS lesions sprouting like plague buboes or syphilis poxes, a terrifying harbinger of death to come. Clusters of cases appeared in cities with a large population of gay men – Los Angeles, New York, and of course, San Francisco.

Like the Chinese immigrants, poor people, and sex workers of yore, gay men were vilified and demonized for AIDS. Right wing pundits zeroed in on promiscuity, blaming the disease on immorality. Cops, paramedics, and nurses refused to handle or treat AIDS patients. Since it was characterized as gay disease, there was little interest in funding research or finding a cure. As the disease began appearing in other populations – heterosexuals in Haiti and Zaire, blood transfusion recipients, and IV drug users – gay men were blamed. They began to worry that they’d be quarantined, isolated, arrested, or blacklisted for being gay. They didn’t want to end up in a modern Pest House.

In the cities with affected gay populations, only San Francisco had the political will to take action. While Reagan’s federal government dithered and made NO HOMO jokes at press conferences, activists in San Francisco pushed Mayor Dianne Feinstein and public health officials to get to work. In the 1980’s, San Francisco spent more money on AIDS research and response than the federal government, and twice as much as New York City, which had far more cases. While nurses and paramedics refused to treat AIDS patients, San Francisco General opened Ward 5B, a dedicated AIDS unit. Ward 5B (Now Ward 86) was staffed by activists, volunteers, and gay nurses and doctors who served their patients with dignity and compassion.

San Francisco was also – infamously – the first city to close the bathhouses. Bathhouses were orgy central, providing infinite opportunities for anonymous sex, but also AIDS transmission. Public health authorities believed that closing them would slow the spread of the disease, but many in the community saw this as a prudish overreaction. Constant fighting between the close and no close factions delayed the inevitable for years. “And the Band Played On,” an incredible history of the early days of AIDS, nailed this controversy as an *only in San Francisco* fight. As in, only in San Francisco would EVERYONE be focused on protecting gay men’s health, but also calling each other Nazis based on which position they supported.

Speaking of specious Nazi comparisons – experience with AIDS informed San Francisco’s response to the COVID 19 pandemic. The city was the first to issue a stay at home order and close businesses. It’s likely that the institutional memory of the horrors of AIDS made it easier to make those hard decisions in March 2020. There is a high level of respect and cooperation between public hospitals and the health department, forged in the 1980s and 1990s, and the city learned how to take initiative and move faster with a conservative, science-denying federal administration in the way. Obviously there was controversy, and we are dealing with post-lockdown loss of business, but our experience with AIDS does help explain how the city was able to move so fast.

As we’re slowly putting our lives together after a global pandemic that killed millions of people, I think it’s critical to look at the big picture. In my work, I often talk about the parallels between earlier historical events and the present day, but it’s usually in a negative way. It’s usually a SAME SHIT DIFFERENT DECADE kind of analysis, but in the case of San Francisco’s response to disease, I think we’ve actually learned. The diseases of the 19th century exacerbated race and class discrimination, their responses fueled by fear and ignorance. In the 20th century, prejudice against gay people in the AIDS epidemic led to neglect and mass death across the country, but San Francisco managed a caring and innovative response. We saw plenty of racist anti-Asian rhetoric around COVID-19, here and everywhere else, but the city was able to mount an effective response to the epidemic. As with AIDS, we moved faster and more effectively than the federal government. These epidemics built upon each other, and for once the horrifying legacy of early mistakes seems to have laid the foundation for a better future here. Now go wash your hands for 20 seconds.