It’s Oscar season, and I watched Guillermo Del Toro’s movie adaption of Frankenstein with an eye toward . . . body snatching. I read Mary Shelley’s novel when I was a baby English major back in the days when you could smoke in your apartment while writing 30 page papers agonizing over one paragraph in a novel. As I recall, we talked mostly about the classic, enduring themes of the book: technology and alienation, love and death, probably the Alpine scenery and the sublime. When I watched the movie last week, all I could think about was where he got the body parts.

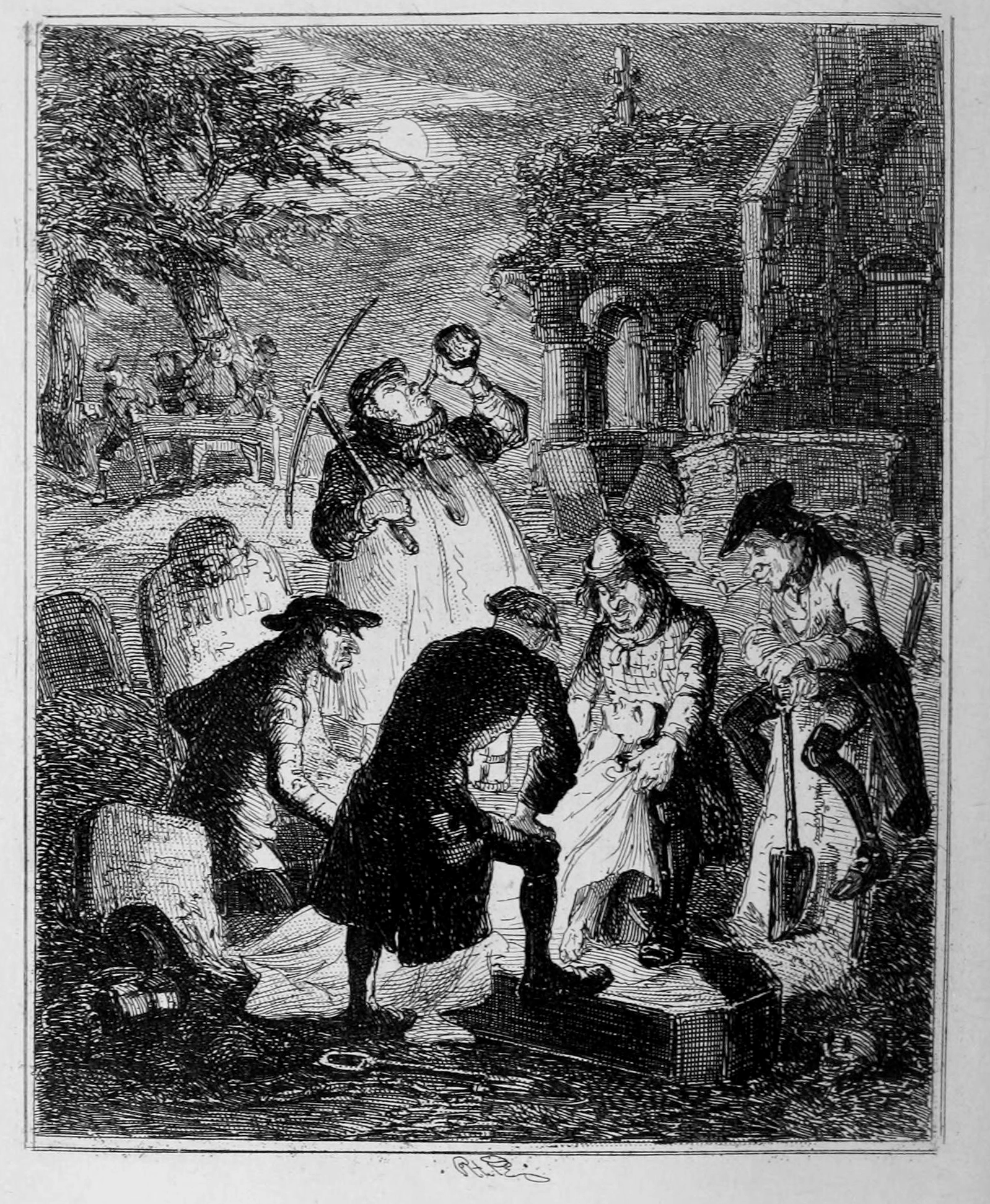

Me, when I have to be responsible for The Horrors I’ve created

This is because I have developed a very niche special interest in early anatomists and body snatching. GIRLS NEED HOBBIES!!! Here on HLAS, and on our new podcast, Dead Reckoning, I’ve been talking about how early medical studies relied on a supply of dead poor people. Watching Frankenstein at Opera Plaza with popcorn and a rosé, I was like – “did she know about anatomists?? Is she making some kind of commentary about that?? AM I AN ENGLISH MAJOR AGAIN????” So I did what anyone with a blog would do – I got out my annotated copy of Frankenstein and started highlighting references to cemeteries and crypts.

I think you’d have a hard time arguing that Dr. Frankenstein isn’t inspired by anatomists and body snatching, and while that’s not the only thing to take away from this book, it’s definitely nestled firmly within the arguments about the dangers of technology and who pays the price for advancement. Dr. Frankenstein did unnatural things with dead bodies, and unleashed a daemon on the world – one that he refused to acknowledge or take responsibility for – and innocent people paid with their lives. Likewise, the relentless, insatiable press forward in medicine in the 18th and 19th centuries required doctors to do unnatural things with bodies, often committing crimes and even killing innocent people to get what they needed, and funding the advance of modern medicine with the bodies of the poor.

Mary Shelley lived at a time when bodysnatching was common. She hung out in cemeteries where she may have seen evidence of it. Her family was surrounded by the natural philosophy heavyweights of the time; they would surely have discussed subjects like this. Her characterization of Dr Frankenstein’s methods of retrieving “materials” line up with the methods we know the bodysnatchers employed. And since I have made myself an amateur historian of STEALING BODIES FROM GRAVEYARDS TO SELL TO DOCTORS, allow me to tell you all about it.

A note on the language: I’m going to refer to Victor’s creation as the creature, not the monster, because the real monster is Victor Frankenstein and THAT’S CANON. I will brook no opposition here.

The History of Body Snatching

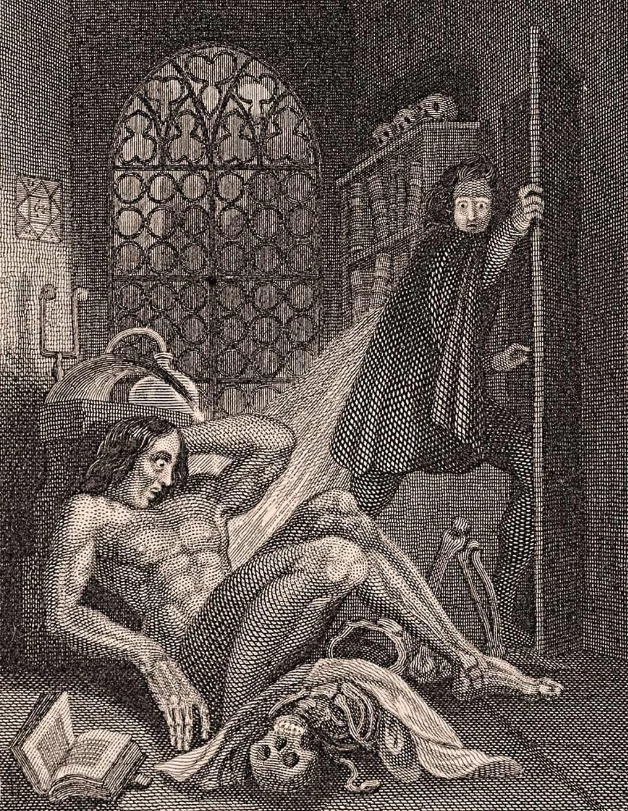

Today it’s widely understood that Frankenstein’s creature is made of looted human corpses. Del Toro’s movie makes it explicit, but Shelley’s original text is more vague. She implies it with Victor’s nighttime prowls around graveyards and charnel houses, his fixation on death, and the gray and yellow cast of the creature’s skin and eyes. We know that Victor uses electricity as his animating force, but she is not specific about what he used to form it. She refers darkly to his “materials,” but he doesn’t call them STOLEN DEAD BODY PARTS. This may have been a little too far for an eighteen year old writing in 1818, lol.

Using corpses for scientific endeavors was exactly what surgeons were up to in the 19th century. In fact, the modern practice of medicine is rooted in anatomical dissections from that time. Dissection required bodies, and for the most part, surgeons did not obtain them in what we would today think of as an ethical manner. They mostly stole or extracted them from the poor and working class. Medical dissection – the process of cutting open a dead body to study it – began in the 1700s, but really picked up steam in the 1800s, when Mary was living and writing.

Initially, the law allowed only the bodies of people convicted of murder and executed by the state to be used for anatomical study. It soon became clear, however, that this was not enough of a supply. The anatomist industrial complex demanded more, so people began to steal them. Now, surgeons were upstanding members of the gentry and would never sully their delicate cutting hands with the dirt of the grave, so they hired BODY SNATCHERS to do it for them. The body snatchers would stalk graveyards for the freshly buried dead and dig them up to sell. Several thousand bodies a year were stolen and sold for dissection, and this was very upsetting to the public. Obviously.

In 1828, the incredible demand for bodies caught up to the ingenuity of the criminal underworld with the case of Burke and Hare. William Burke and William Hare decided to short cut the nasty work of digging up corpses by simply murdering people and selling their fresh remains. They murdered at least 16 people in Edinburgh before being caught and punished. At the time, Edinburgh was the center of anatomical and surgical training, and the public took their anger out on everyone involved.

The public outrage finally convinced Parliament to do something in 1832. It passed the Anatomy Act, which allowed the surgeons to use the bodies of poor men and women in the workhouse as cadavers for dissection. Problem solved! Just kidding, go listen to our episode on this cruel and arbitrary policy.

Mary was a Goth

Mary Shelley was an OG Goth. She is our Queen Mother! She was deeply interested in death and loss, probably because she lost her own mother as an infant. Her mother, Mary Wollstonecraft, was a women’s rights pioneer, intellectual, and a free spirit. Wanting to connect with her mother, and be inspired, Mary spent a lot of time in cemeteries, where she could easily have seen body snatching in action.

In particular, Mary spent a lot of time at her mother’s gravesite, which is peak Goth behavior. Wollstonecraft was buried at St. Pancras Churchyard, a place that known as a body snatching hotspot. St. Pancras is out by Kings Cross, and at the time it was rather isolated and quiet. A good place for Mary to write, journal, and allegedly have sex with her boyfriend Percy, but also ideal conditions for stealing bodies at night. If we really want to get into the weeds here, she and Percy would have been doing the deed on her mother’s grave (ALLEGEDLY!) at night, the same time the resurrection men were active.

There are plenty of contemporary references to St. Pancras, and its body snatching problem, to back this up. In 1728, a periodical called A View of London and Westminster: or, The Town Spy, &c. reads “The Corporation of Corpse-stealers, I am told, support themselves and Families very comfortably; and that no one should be surpriz’d at the Name of such a Society, the late Resurrections in St. Saviour‘s, St. Giles‘s, and St. Pancras‘s Churchyards, are memorable Instances of this laudable Profession.” In 1813, authorities caught and prosecuted a body snatcher gang St Pancras. A popular satirical poem by Thomas Hood called “Jack Hall” (pronounced “jackal” – get it?) about body snatching in St Pancras published in 1827 captures the zeitgeist. In it, the bodysnatcher dies and is pursued by a flock of vulture doctors who want his corpse now.

Body snatching was extremely unpopular and seen as a real social problem at the time – Mary would have heard these stories and they had to have been on her mind while at St. Pancras.

A Circle of Anarchist Philosophers

Mary Shelley’s father, William Godwin, was a philosopher who supported the rights of women and made sure his daughters were educated and informed. From a young age, Mary was surrounded by her father’s influential circle of scientists, philosophers, and poets. Her education in “natural philosophy” would have included cutting edge topics of the time – medicine, anatomy, electricity, politics, and metaphysics. These men would absolutely have been engaged and familiar with anatomy, surgery, and the issues around acquiring bodies.

Some of Godwin’s cohort are especially noteworthy – and frequently cited – because their influence on Mary’s work is so clear. William Nicholson was a chemist who studied electricity and pioneered the use of electrolysis in water. He also wrote and edited scientific texts. Humphrey Davy was a chemist who originally apprenticed to become a surgeon. His research is a fascinating amalgam of ideas referenced in the book – tanning (preserving flesh), surgery (which required dissection), and electricity (animating). Frankenstein’s creature is brought to life using some kind of electrical process, which was a popular idea at the time, and must have been informed by proximity to these thinkers.

Godwin himself studied psychology, the scientific method, ethics, determinism, utilitarianism, materialism, and political philosophy. He was interested in justice and fairness, and once debated friend of the pod Thomas Malthus, arguing for better rights and treatment of the poor. He had an interest in the metaphysical, favouring the possibility of “earthly immortality” – something the creature is granted by Dr. Frankenstein. His friend, the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge was a founding member of the Romantic movement, a literary scholar and philosopher, who wrote about similar subjects. Mary was reportedly deeply influenced by his eerie prose and makes numerous references to his most famous poem, Rime of the Ancient Mariner, in her book. Mary could have absorbed stories about how the dead were treated, used, and the ethics of that from her time around these dudes.

His Dark Materials

Victor Frankenstein is a doctor, and he’s trained in anatomy. In the early 19th century, that would have meant dissecting corpses to learn from them – but that’s not all. Early anatomists had to find their own bodies; they weren’t necessarily provided by the medical school. That meant buying remains from shady characters, lurking around disgusting hospitals for someone to die, and bribing workhouse managers. Anatomists at this time were absolutely aware of where their materials came from. Victor would be no exception. As he tells us, “To examine the causes of life, we must first have recourse to death. I became acquainted with the science of anatomy but this was not sufficient; I must also observe the natural decay and corruption of the human body.”

In the book, Victor lurks around graveyards at night, looking for inspiration, but probably also MATERIALS. He repeatedly reminds us that he’s not superstitious, so he’s not afraid: “In my education my father had taken the greatest precautions that my mind should be impressed with no supernatural horrors. I do not ever remember to have trembled at a tale of superstition, or to have feared the apparition of a spirit.” HAHAHAHA JUST WAIT BROTHER.

At first, his excuse to be in the graveyards at night is to study death.

“Darkness had no effect upon my fancy; and a church-yard was to me merely the receptacle of bodies deprived of life, which, from being the seat of beauty and strength, had become food for the worm. Now I was led to examine the cause and progress of this decay, and forced to spend days and nights in vaults and in charnel houses.”

“One secret which I alone possessed was the hope to which I had dedicated myself; and the moon gazed on my midnight labours, while, with unrelaxed and breathless eagerness, I pursued nature to her hiding places. Who shall conceive the horrors of secret toil, as I dabbled among the unhallowed damps of the grave.”

He’s pursuing death down into its hiding places, and those are probably newly dug graves. His secret toil may very well be the bodysnatcher’s special method – cutting a hole in the top of a coffin, putting a rope around the neck of the deceased, hauling them up, stuffing them in a sack, and running away.

Victor finally admits that he “collected bones from charnel houses; and disturbed, with profane fingers, the tremendous secrets of the human frame,” and took them to his “workshop of filthy creation.” There, “the dissecting room and the slaughter-house furnished many of my materials; and often did my human nature turn with loathing from my occupation.” Later in the book, as he makes an attempt to create a mate for the creature, he describes the lonely, isolated spot in the Orkneys where he can work undisturbed toward this “filthy process,” pursued “in cold blood,” his “heart often sickened.” The process is filthy and disheartening for many reasons, not the least of which is he’s cutting up stolen corpses. In a hut on the beach. This is why we love Gothic literature, you guys.

The creature himself certainly sounds like he’s made of the waxy, dead flesh of recently unearthed corpses. His eyes are yellow, as is his skin. He has a full head of glossy black hair which to me is a reminder of the legend that hair continues to grow after death. Victor describes him as a “mummy” and “my own vampire, a spirit let loose from the grave.” Given that everyone who sees the creature is frightened half to death, a stitched up yellowing giant that gives off mummy vibes, materials being decomposing body parts is plausible.

Mary’s Travels and GDT’s vision

Mary’s travels as a young woman put her in proximity with body snatching hot spots – as only the true Mother could. She spent time in Scotland, the capital of anatomy education and the site of the Burke and Hare affair. She also traveled through war torn parts of Europe, where she may have seen dead bodies being looted in the aftermath of battle; or at least, heard about it. These circumstances don’t come up in her original text, but Guillermo del Toro uses them to great effect in his film adaptation. Del Toro takes us to the places where bodies of the poor, criminal, and war dead would be likely to be snatched. Starting with the surgeon’s operating theater.

That tickles

To me, the best scene in the entire movie takes place in the dissecting/operating theater. There, Victor displays how he uses Galvinism – electricity – to animate a partially stitched together ragdoll of a human torso. It’s HORRIFYING and Del Toro does SUCH A GOOD JOB WITH IT. First of all, this is clearly anatomist shit! It’s a convening of doctors, in a theater, and Victor is demonstrating his technique. He explicitly tells his audience that the torso of this unhinged horror movie mannequin is from the body of a shopkeeper – delivered “minutes” after expiring. There is no scene more chilling in the entire movie than when that disembodied torso gets a jolt of electricity, wakes up, and gasps in fear. This, my friends, is foreshadowing. You SHOULD BE APPALLED.

The Victor of Del Toro’s movie is shown harvesting his materials from different body snatching venues than the damp crypts and worm holes of the book. First, he attends a public execution, where he studies the condemned for the right type of materials. He wants one with a strong back. This is an allusion to the very real practice of buying bodies directly from places like Tyburn gallows – something that surgeons may even have done themselves. Prior to the Anatomy Act, this was the only legal place to acquire bodies for dissection, and riots frequently broke out over the best specimens. Also present in the scene is a howling, chaotic mob of souvenir seekers – the blood and parts of hanged men were purported to have magical properties.

Victor also searches for body parts on the battlefield with his accomplice, Harlander. The character of Harlander is a former army surgeon, who would absolutely have trained on live and dead soldiers. We see them scouring the battlefields of Waterloo, looking for bodies that weren’t too mangled and have “long limbs,” presumably to go with that strong back. I haven’t found evidence of body snatchers at battle sites, but I know that this was proposed as a supply in England. We also know that after major battles, the conquering army and a flock of camp followers would routinely strip the bodies for valuables and teeth. I’m sorry to tell you, but those teeth were used to make dentures for the living. Hug your invisalign providers, guys.

Del Toro’s Dr. Frankenstein lays all of his materials out in a bloody morgue/lab in his Gothic castle, in scenes that remind me of both an anatomy lab and an early surgical theater. Blood floods the room, parts lay scattered about, and Del Toro makes explicit what Shelley only alludes to. It’s 213 years on, but the horror is still visceral – even more so when you realize that the science and medicine we take for granted today also stands on the shoulders of the mangled, bloody poor. The whole project is about remembering the cost of advancement, taking responsibility for what we have created, and the hubris of playing God.

This is Fine

Sources

The Doctors’ Riot of 1788: Body Snatching, Bloodletting, and Anatomy in America by Andy McPhee

Death, Dissection, and the Destitute by Ruth Richardson

Dead Reckoning Podcast Ep 3: The History of Medical Cadavers, Never Enough Bodies!

Frankenstein, Annotated for Scientists, Engineers, and Creators of all Kinds [this is the text I used!]

The Study of Anatomy in England from 1700 the Early 20th Century – PubMed